Interview with Writer and Director Nick Lane

What are the main challenges of adapting The Valley Of Fear for the stage?

Expectation certainly. Bringing Holmes and Watson to the stage is a joy but one I treat with a lot of care, as audiences necessarily have expectations about how Doyle’s famous creations should be portrayed.

Beyond that, the key challenge is structure. Now, a common four-stage structure to Holmes mysteries is the set-up, the investigation, the reveal and then the explanation. In the full length novels this last part, wherein Doyle gives his recently outwitted and captured antagonists the chance to explain the motives behind their crimes, is regularly the longest chapter in the book. In The Valley of Fear it’s not just one chapter, it’s a story in its own right, taking up over half the book.

The two parts – The Tragedy of Birlstone (i.e. Holmes’ investigation) and The Scowrers (the background to the crime) – are split. On subsequent readings one can see how much the first part feeds the other but on a first pass the stories appear barely connected at all. I suspect this is because Doyle had long since harboured a desire to write about the Molly Maguires (an organised crime syndicate formed out in the coal states of the US) and decided to incorporate his story as part of a Holmes mystery, thus guaranteeing it wider readership than it might otherwise have gotten. However true that is, it is quite a departure for the series of mysteries – an entirely different plot, and one that doesn’t involve Holmes at all!

Which leads us back to the choice of novel and the approach to adaptation. The question I asked myself when sitting down to structure it out was simple – if I retain the structure of the novel (and each part’s length relative to the other), what would an audience who had paid to see a Sherlock Holmes mystery make of the hero disappearing before the interval, his story usurped by characters they’d hitherto never met…?

How have you overcome that challenge?

I felt that in bringing the book to the stage I had to alter the structure of the novel – I knew I wanted to keep Holmes, and of course Watson, at the centre of the experience from first to last. Partly this was to satisfy audience expectation, but partly I’d say it was to give audiences unfamiliar with the novel a clearer idea of why the second story is being told at all. It is, in my opinion, as thrilling a piece of writing as the case Holmes and Watson are attempting to solve, and I wanted to honour that whilst also trying to avoid dropping our two central characters. In our adaptation then, we move – hopefully seamlessly – from Baker Street and Birlstone House in 1895 to the Vermissa Valley in the US, twenty years earlier. The idea is that each of the more modern sections has an echo of the events in the past, and just as one mystery is being revealed to us by the great detective, so another reveals itself…

As well as altering the chronological order in which the scenes are viewed I also found the narrative beats within both parts of the novel to be not dissimilar and I thought we could be smarter than that. I’m not saying that I was attempting to somehow be cleverer than Conan-Doyle (anyone who knows me will know that I can, on occasion, be outwitted by a toaster); I’m simply saying that, when shuffling the deck as I have, the similarities between the ebbs and flows of each story were far more noticeable and I was keen to give each section its own pulse.

We can arrive at some of this externally, of course – separate to the writing, there are ways in production that we can ensure the audience are clear as to which story we’re part of. Lighting can give us different hues; the accents of the characters are naturally a big hint… and then there’s the score. Working with a composer like Tristan Parkes – who has such a breadth of knowledge regarding music history – gives us the chance to paint two very distinct pictures with sound.

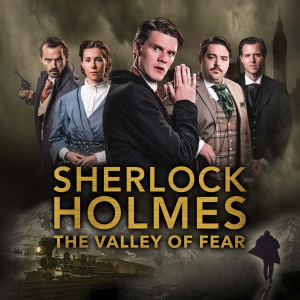

What can you tell us about the cast?

It was delightful to be able to welcome Luke Barton and Joe Derrington back to the roles of Holmes and Watson respectively, roles they played to great acclaim in The Sign of Four. Writing the scenes between the pair was so much easier this time around, knowing we could build on their terrific chemistry. My introduction to Sherlock Holmes came with my nana when I was a little kid; watching Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce’s movies on Saturday afternoons on BBC2. For me, I always thought Rathbone and Bruce would be Holmes and Watson… until I worked with Luke and Joe.

Another face familiar to recent Blackeyed audiences joins Luke and Joe – Blake Kubena, who only just finished the tour of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde as the title character(s). Blake is originally from Houston, Texas – I knew part of the book was set in the States and once I’d read it, Blake’s easy charm and excellent physicality on stage fit the lead role in that section of the story perfectly.

As for the other two company members, Alice Osmansky rounds out the regular characters at 221B Baker Street, playing the lively and intelligent Mrs. Hudson as well as a number of other roles. Gavin Molloy will play a host of other characters, including the quietly dangerous organised crime boss, Jack McGinty. Both Gavin and Alice are terrific actors and I’m delighted to have the opportunity of working with them.

How does Moriarty feature in the adaptation?

This is something that people who’ve read the Sherlock Holmes stories know already, but those whose connection with this world is through film, television and radio might be surprised to learn that Professor James Moriarty physically appears in only one Holmes mystery, The Final Problem. He is mentioned in five others, I think (including The Valley of Fear) and in each of these his presence is that of an ‘éminence grise.’ Perhaps it was inevitable that makers of films and television, sought out ways to bring this character, depicted as every inch Holmes’ intellectual equal, more to the forefront of Holmes’ world. Arch enemies are fun, after all. And they’re great to write for.

As far back as the earliest discussions, Adrian and I talked about finding a way to bring Moriarty into the adaptation. I think it’s interesting for those who know Conan-Doyle’s work to see him cross Holmes’ path, and if it’s something that will surprise those that know the novel I would hope the surprise is a pleasant one.

How do you see the relationship between Holmes and Watson?

Something that always intrigued me about the dynamic between the great detective and his trusted partner-in-detection is the depth of their friendship. It’s a misconception born of Holmes’ genius that Watson is an intellectual lightweight – I’ve always thought of him as very smart. He just happens to keep company with someone even smarter. It must be like getting into Cambridge to study Physics, only to discover you’re working and rooming with Steven Hawking!

I’ve always loved the banter between the pair of them too – competitive at times but never cruel. Holmes, it might surprise those used to more modern interpretations of the character, is logical, yes, but also rather warm. So in this adaptation I wanted to explore that; to test it a little. See how much pressure the pair can take before they cease to be a pair. Can they exist without one another?

How close is this adaptation to the original novel?

In my opinion, the plot is an important roadmap and you veer from it at your peril, but I think more important than that is the tone and the intention – the energy, if you like – of the original material. What works in a novel, if taken directly to the stage, could become ponderous and, at worst, a little dull. In order to alleviate that problem, while still remaining true to the author’s work, certain alterations can and must take place. Ultimately what you want to make is something entertaining but undeniably theatrical. Try to compete with the theatre of the mind created by readers when they invest their own imaginations in a novel is a losing battle, I think – every successful adaptation I’ve seen has very much been its own thing, whatever the scale.

What should we expect in terms of the style of the play?

What’s great about the Holmes adventures, for those who don’t know (and there can’t be many of you), is that Conan-Doyle wrote the vast majority of them – all but four – from Watson’s point of view, which allows us the opportunity, through the character of Watson, to break down the fourth wall and admit to the theatricality of the experience. From that point, once the audience is aware of the game being played, I think it’s easier to accept actors playing multiple roles. Multi-role playing is vital to the telling of the story given the cast size (and besides which, having learned as a writer under the inimitable John Godber, multi-role theatre is something I’m familiar with and love), and we’re lucky to have a cast experienced with that style of performance.

Beyond the theatrical style in which we present the two mysteries, what I’m excited about is exploring how the Holmes scenes and those set in the US are played. Will they be physically different? Linguistically? Will the energies brought to the separate locations and situations be similar enough to belong together while offering the audience different textures or flavours? It’s certainly what I’m aiming for!

How have you set about writing a genius?

What can I say about Sherlock Holmes’ intellect that hasn’t been written, shown or illustrated before? And how does a daft bloke from Doncaster approach bringing the great detective to the stage?

Well, it goes without saying that Conan-Doyle does a lot of the heavy lifting here – the detail of his analytical process and personal idiosyncrasies are there on the page, but you have to be careful with how you use it, I think. Victorian prose can be extremely wordy and the last thing you want to do is overload the script with direct lifts from the page. I touched on this before but the danger in doing that is that you might render one of the most iconic characters in British literature somewhat dull. So you have to pick and choose what to use, what to highlight… and what to add to move the plot along in a satisfying and theatrical way. That’s what I found with the previous adaptation The Sign of Four and it’s just as true here.

And then when you add the other towering intellect of the Holmes adventures – the oft-mentioned, always feared but rarely seen Professor Moriarty – you’ve got to be doubly careful. Writing a scene between the two characters was as much about what they weren’t saying as what they were, and I’m really thrilled to see how it develops in rehearsal between Luke’s Holmes and Gavin’s Moriarty.

Sherlock Holmes: The Valley Of Fear will be performed at South Mill Arts on Friday 28th & Saturday 29th April, 7.30pm (Tickets: £19 | £17 Conc.)

Tickets are available here: https://bit.ly/3KZzwfE